Photo by Clemens v. Vogelsang/Flickr (licensed under CC BY 2.0)

By Brandon S. Brown

There was a period in time when I thought my life would be defined by one thing. One instant. One terrible mistake. I had almost instantaneously accepted the role assigned to me—the verdict of guilty, the label of felon and inmate. With this label I had been given, I had now entered into the category of “the other.” What could I possibly do about it?

When I was growing up I viewed crime the same way most people do: a story in the news, something that happened in the neighborhood, or the actions of people I couldn’t identify with. It’s embarrassing to admit that even when I was out on bail, awaiting the trial that would decide my fate, I still read the articles about criminals being sentenced and believed they had gotten their “just deserts.” Even as my future hung in the balance, I still couldn’t identify with the people I assumed were going to prison because they were “bad.”

Then I became one of those people.

In fact, as I sit here now, I am one of those people. I was arrested in 2008 and have spent more than ten years of incarceration trying to understand who I am, what my role in this world is, and how I can possibly make it a better place after prison despite all that I will face as “the other.”

It may be interesting to some that I am not just an inmate, but also a graduate student at George Mason University’s School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution. Looking back, it feels like all the events of my life were leading me here: a young man searching for a place to fit in; a journey through the criminal justice system; the chaos of arriving in prison; countless hours of silence, introspection, and a sense of wonder that education has provided to me. I was quite lucky to earn my associate’s and bachelor’s degrees in Liberal Studies while incarcerated; the experimental philanthropy of the sister of a well-known investor gave me an opportunity to rise above the label that I believed I had to adopt.

During my undergraduate work I was able to focus much of my studies on U.S. history, genocide, and Holocaust and human rights studies. A history of genocide class taught by an amazing professor, Dr. Robert Bernheim, captivated my interest, pulling me towards this area of study, and over time, the combination of these classes caused something profound to happen within me. I began to realize how much pain exists in the world, how conflict is everywhere, and how stereotyping, labeling, and classifying people as “other” has led to some of the worst conflicts that history has recorded.

While learning about the history of genocide and the Holocaust, I was introduced to an incredible film called “As We Forgive” about the process of discovering reconciliation in post-genocide Rwanda. Shortly afterward I met a man named Fred Van Liew, and we began discussing something called “restorative justice.” Reading his book, The Restorative Justice Diaries, changed the way I viewed my experiences with “justice,” and months later, I took a course towards my undergraduate degree specifically about this concept of restorative justice. It was in this course that I discovered Howard Zehr’s Changing Lenses: Restorative Justice for Our Times, and I was forced into realizations about harm I had committed and how the criminal justice process had not accomplished any resolution, but in fact had likely made things worse for everyone affected.

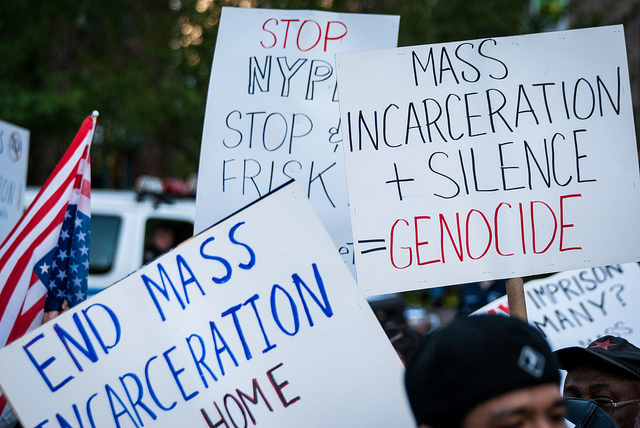

Learning about an alternative form of justice forced me to become more cognizant of the history of incarceration in our country. Books like Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, and William J. Stuntz’s The Collapse of American Criminal Justice, opened my eyes to the numbers of people that we imprison (currently 2.3 million people incarcerated, more than almost all other developed nations combined). I realized that the system does not create healing in any capacity, but instead pits people against each other in a game where someone is supposed to “win,” even though rarely is any meaningful victory achieved. Justice becomes about “The State of ________ vs. Defendant’s Name Here”—nowhere is a victim even mentioned. The process focuses more on which side can tell a better story; facts often go by the wayside. Guilty people go free, innocent people go to prison, and when “justice” does prevail, both victim and offender exit the courtroom to be forgotten by the people who fought so diligently on their behalf.

Justice has become impersonal. Justice hurts.

In my second year of prison, I also entered my second semester of college classes. I realized a level of freedom that I had never experienced even in the 21 years of life I spent outside the fences. My mind had been effectively liberated, and my heart was made free. When I was finishing my undergrad, I came up with a crazy plan to write letters to schools in an attempt to convince them to allow my application for graduate studies. I wanted to study peace—the very thing I had disrupted as a misguided young man. I desired to learn how I could rise above my mistakes and the labels I will surely endure after prison, in order to find a voice that could speak to healing instead of hating, dialogue instead of debate. I wanted to discover my voice.

George Mason University and S-CAR have given me an opportunity to make that discovery. They have looked at my mistakes, but also at my humanity, and I have never been more thankful for anything in my life. Halfway through my first semester as a graduate student, I have found an even more profound sense of freedom, and I have found a community that feels like home. The possibilities seem endless now, and as I uncover the history and the theories of conflict, I feel that my journey is just beginning. The possibilities feel endless to me, and peace is the mission.

Perhaps as I continue to learn about the legacy of individuals like Johan Galtung, Elise Boulding, Carolyne Stephenson, Gene Sharp, and the myriad other practitioners who have changed the face of how we study and address conflict, I will begin to see a path that will allow me to make a difference. Maybe my voice will be one that speaks to a better way to “do justice.” Could I help create a system that addresses conflict and harm in a way that brings people together as opposed to creating ever deeper societal rifts? One thing I have discovered already, under the mentorship of the amazing Mason and S-CAR community, is that I have taken the necessary first step.

The world is full of inspirational people who took a chance, told their story, and dedicated themselves to a cause. Although my story is incomplete, I am willing to share it. I feel incredibly dedicated, and Mason has offered me a path. The rest is out of my control—and I’m okay with that.